The Outlaw Country Jew: After 40 years, Augusta native Daniel Antopolsky is recording albums

Townes Van Zandt, Susanna Clark, Guy Clark and Daniel Antopolsky on the porch of the Clarks’ East Nashville home, in an iconic 1972 photo

One of the most iconic photos in country music history shows four “outlaw country” musicians on a porch in 1972 — the legendary Townes Van Zandt, who died in 1997, artist and songwriter Susanna Clark, who died in 2012, and songwriter and performer Guy Clark, who died in 2016.

What happened to the fourth person on the Clarks’ porch?

Since the 1980s, the only Jewish member of the outlaw country movement has lived a simple life on a farm near Bordeaux, France, a world away from the drug- and music-fueled scene of the early 1970s where he admits to never quite fitting in.

After dropping out of the music world for decades, Daniel Antopolsky, who grew up in the Jewish community of Augusta, Ga., recently recorded a selection from the hundreds of songs he has written, releasing his first albums.

In the early 1970s, Antopolsky toured with his friend, Van Zandt, and is widely acknowledged to have saved Van Zandt from a heroin overdose in Houston in 1972. Doctors said that had Antopolsky brought him to the hospital just two minutes later, Van Zandt would have been gone. Before long, Antopolsky would escape that scene, but the songs would keep coming — without an audience.

He explains his decades on a farm in France by stating “we’re country Jews. We like being in the country.”

His family didn’t start out in the country. After World War II, his family got a farm outside Augusta and spent a lot of time fishing and walking around in the woods. During those walks, he and his father would plant a lot of trees. His father had grown up on Delancey Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. “He never saw a tree until he was 12 years old and the family moved to Waynesboro, Ga.,” Antopolsky said.

His family had “an old-fashioned hardware store on Broad Street” in Augusta, unlike other relatives and community members who were in the “shmattah” business. Their clients ranged from rich to redneck, and they sold copper sheets to bootleggers who made stills with them. “Just a bunch of great people,” he reflected.

There were many characters who would later influence his songwriting. “Southerners could tell stories and yarns,” he said. “I liked that, and I think that’s where I got some of my language and put some of it into songs.”

Among the “good old guys, people you feel comfortable with” was an African-American man who always wore six or seven coats and six or seven pairs of pants. When he finally asked about it, the man explained that “what keeps out the cold keeps out the heat.”

He’d also hear stories from the bootleggers, recalling one who explained “Look, Daniel, that’s why my thumb is gone.”

Also influencing his musical evolution was a nanny who listened to Gospel music. “It’s not the same as being brought up in New York City,” he observed.

Antopolsky started writing songs in the late 1960s. When he was 14, his brother gave him a guitar, and “there were a lot of people a lot better than me.”

His mother died when he was 10, and had been unable to talk for six years before that. He would go to Hebrew School four days a week, and accompany his father to minyan for Kaddish. “I loved those guys,” he said. “Old European guys singing and banging on the table,” and one guy who could sing in harmony.

His father died when he was 17, so by the time he wound up at the University of Georgia, “I didn’t have anyone to come home to for Passover or Yom Kippur.”

Despite enjoying his heritage, he “left it all” and experimented with different spiritual paths. Like so many Jews, he tried yoga, then learned about Hinduism. “There was a time I thought I wanted to be a Christian,” he admitted.

Armed with a degree in public relations from the University of Georgia that he would never use, Antopolsky became a long-haired, beaded hippie. At the university, he met Van Zandt. They became friends and Antopolsky went with him on a national tour.

One oft-cited story is that they were in Dallas at a motel, and found the street was blocked off due to a revival. They challenged each other to write a song in 30 minutes and then sing it. Van Zandt stayed in the motel while Antopolsky sat under an oak tree outside.

Van Zandt’s composition was “Pancho & Lefty,” which became one of his most famous works, and some say Lefty was modeled after Antopolsky.

Antopolsky’s song was “Sweet Lovin’ Music,” which would become the title track of his debut album 40 years later — that day in Dallas, Van Zandt had suggested Antopolsky use that as the name of his first album.

But he never quite fit in with the drug-fueled outlaw country scene. Over the years “I lost a lot of friends who were musicians,” dying of a mysterious illness that later was identified as AIDS. “Nobody knew what was the matter” with them.

What saved his life? “I’ve been a chickens–. I’ve had a fear of needles,” so he never shot drugs. “I was afraid… I would sniff it, smoke it or swallow it. I’d never shoot it.”

The then-unknown dangers of sharing needles was just the half of it, he said — between hits the needles were often stuck into a dirty dart board.

With his spiritual searching and a much more whimsical and optimistic outlook than his contemporaries, he was also turned off by the rough competition of the music industry in Nashville, and decided to get away. He traveled the country and the world, ending up back in Georgia.

Returning to Augusta, he met the woman who would become his wife. “I’d never dated a Jewish girl,” he said. Sylvia was a Jewish student from France who was brought to Augusta for a residency.

She explained that Robert Greenblatt, a noted researcher at the Medical College of Georgia, had established a relationship with the Bordeaux gynaecology medical school. A Montreal native, Greenblatt was a Francophile, and Greenblatt’s successor, Edouard Servy, brought Sylvia to Georgia on a research fellowship in fertility and endocrinology.

Antopolsky met Sylvia at a party and they started dating. When she had to return to France for two more years of residency, he followed her.

At the time, he said, “Broad Street was dying” and Antopolsky Brothers Hardware had not followed other retail establishments to the outskirts of town. “I’m just a guitar player, I’m a dreamer,” he reflected. “I’m not that good at doing a hardware store.”

He moved to France, and his brothers closed the store a few years later. The building now houses The Pizza Joint, and Antopolsky had lunch there a couple of years ago.

After arriving in France, “first thing I did was get earplugs because I wasn’t used to living in the city,” he said. After his instruments were stolen, they got a place in the country, where he started organic farming and tending chickens. While he was no longer on the music radar, he kept writing songs.

Living in “an old French farm house with thick walls” was useful, because “after everyone goes to sleep, I’d go upstairs until 1, 2 in the morning… I would play as long as I wanted to.”

Inspiration has been everywhere. “I’ll jump off a tractor and write a song” on the side of a box.

After his twin daughters were born, Antopolsky’s passion for his heritage reignited, and he started putting on tefillin every day, keeping kosher and Shabbat, and studying Torah.

On occasion, he would write a Jewish-themed song, such as his 1985 work, “Mama’s Chicken Soup.” “It’s really funny,” he said, but he never performed it. “I don’t have that many songs like that, but I’d sing them to a Jewish audience.”

For years, he figured eventually something would happen with his songs, “but I wasn’t going to do anything” to make that happen. “If there are some good ones, maybe something will happen.”

That something was Jason Ressler, who met Antopolsky and his family at a hummus place in Tel Aviv when they were attending a wedding in 2011. “We had a mutual friend who’d met Daniel in Bordeaux,” Ressler explained, and as he was splitting time between Tel Aviv and Bordeaux, he would “hang out” often with the Antopolskys.

Ressler said he didn’t know about the music for over a year “as he never discussed it and only played live rarely,” like doing cover songs for the U.S. Consulate in Bordeaux on Independence Day. Also, he said, “who wants to hear some guy’s music when you’re friends with him in case it sucks and you have to smile and say it’s great?”

One day on the farm, Ressler heard Antopolsky practicing. “I listened at the door and thought I was listening to some of the best songs I’d ever heard, then I went in and made him play me tunes for hours and told him he had to let me get an album made.”

Ressler intended the project to be for Antopolsky’s family, but it quickly evolved into a documentary film and several albums. “I certainly never meant to become a music manager or expected Daniel to become as big as he’s getting,” Ressler admitted.

Ressler arranged for Antopolsky to meet Gary Gold, a Grammy-winning Nashville producer who has worked with Smokey Robinson, Stevie Wonder, Carlos Santana and Bonnie Raitt. “We knew each other,” Antopolsky said. “Maybe we met each other at Mount Sinai.”

He read some of his songs, many that he hadn’t sung in years. “My children haven’t heard half of my songs,” he said.

Going into the recording studio in 2013 was difficult, with things that were new to him — studio musicians, wearing headphones. “I’d hardly ever done it.”

His chickens, a huge priority for him, also played a role in the Nashville sessions. As the studio date approached, Antopolsky delayed the recordings because one of his favorite chickens was ill.

The Nashville sessions resulted in “Sweet Lovin’ Music,” and “some of the songs turned out great.”

But “when you’ve got chickens and you’ve got children and you’re in the country, I don’t like to go into cities. I’m a country Jew.”

A decision was made to do the next albums in France, in a makeshift studio set up on the farm. “It was fun, and great of (Gold) to come here.” The result was a pair of albums, “Acoustic Outlaw” volumes 1 and 2, which are more simple and rustic, and less polished, matching his personality.

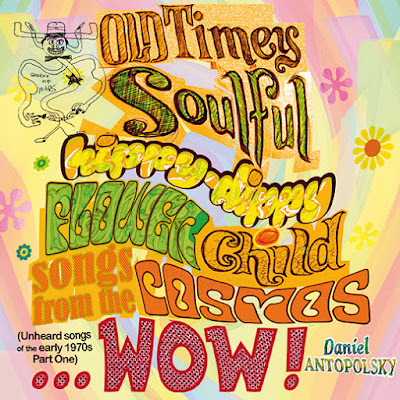

His new album, “Old-Timey, Soulful, Hippy-Dippy, Flower Child Songs from the Cosmos… Wow!” will be released on Dec. 15 and pre-orders are being taken on iTunes.

The new album focuses on songs he wrote during his early-1970s wanderings in places as diverse as the north Georgia mountains, Greece, India, Thailand, Burma and California. Ressler said many of the songs came from the time in Antopolsky’s life when he was rejecting “the darkness of the Outlaw Country scene” and was on “his spiritual quest to find life that matched his optimism.”

Early next year, “The Sheriff of Mars,” the documentary about Antopolsky’s life, will be released. Gold had suggested the film as a way of telling Antopolsky’s story beyond the albums, from growing up in a small Southern Jewish community to his adventures in Outlaw Country, his decades on the farm and his reemergence in the music scene.

The title comes from a character that Antopolsky has drawn since Kindergarten, “a sheriff who came down from Mars to Earth with the express mission of making everyone happy.” In 1975, he wrote a song about the sheriff, and the sheriff makes an appearance on the cover of the new album.

He tries to remain optimistic and whimsical in his writing, even when doing commentary. About his song “Crater Dust,” he said “I’ve looked at America a long time with a microscope… We’ve fallen into a giant crater” of trying to divide people. “We need to start respecting each other.”

While the song’s theme “is not so easy… it comes out optimistic,” he said.

He worries about rising anti-Semitism in France. “France and America are still wonderful places, but you wonder about the future,” he said. “We were in Poland 600 years before it turned bad.”

Though his music career seems to be taking off, Antopolsky is staying grounded. “I have to take it easy now,” he said. “I’m almost 70, and just had heart surgery,” he said. “Baruch HaShem, that was a big deal.” Especially since he had never been admitted to a hospital before.

Because he hasn’t done much performing and “maybe I smoked too much funny stuff,” he has to have the lyrics written down when he does concerts.

“If everything works out, I’m happy to do this, and I’m happy if it can come to something good and be positive in the world,” he said. “If my songs are good, it’s because people gave me more than I give them.”