Memory through food: Alon Shaya re-creates pre-war family recipes for a Holocaust survivor

Historian Edna Friedberg, Steven Fenves and Alon Shaya

Alon Shaya often speaks of the transformative power of food and cooking, and its ability to transport someone across time and around the world. A recent project for the James Beard Award-winning New Orleans chef takes that philosophy to a new dimension.

Shaya visited Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial, while he was on a culinary tour in Israel a decade ago and saw recipes from the Holocaust that were scribbled on the back of receipts or scraps of paper. “I was so moved by that. I was wondering what food meant to people in that horrific time, and what role food played in peoples survival or mental state, how they survived physically and mentally.”

A friend urged him to visit the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, to see what they might have in their archives, and “they had a plethora of recipes that were rescued from the war.” He couldn’t read them, though, as they were in Hungarian, Polish or Russian.

Among the items was a book of family recipes, donated by Holocaust survivor Steven Fenves. Shaya was astonished to learn that Fenves lived nearby and was a regular volunteer at the museum. It was “an opportunity to reach out to Steve and get first-hand knowledge of his memories,” and “if I was really lucky, be able to cook a few of these recipes and taste the food” and make the recipes available for others to use.

“As a chef… I want to cook food that has meaning and stories to it,” Shaya said. “I think that adds to what I love so much about food.”

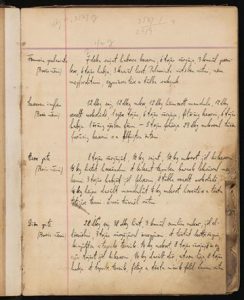

A page from the cookbook

Fenves was a native of Subotica, Yugoslavia, where his father had a publishing house and his mother was a graphic designer, living an “upper middle class” life. The area was occupied by Hungary in April 1941, and a Hungarian officer took over the publishing house, kicking out Fenves’ father. The family had to let their help go, both because of financial reasons and because Jews were no longer allowed to have servants, and Hungarian officers occupied over half of their apartment.

Fenves said they survived by selling off their possessions, including his prized stamp collection.

He suffered “neglect and humiliation” after being one of only nine Jews out of 45 to be allowed to attend school, then in March 1944, when Fenves was 12, the Germans came in. His father was immediately sent to Auschwitz, while the rest of the family was sent to a ghetto before going to Auschwitz. As they were being deported, Maris, their former cook, was in a crowd outside, “competing with the vandals” who rushed in to loot the newly-abandoned apartment.

Maris, who he remembers as “a big strong woman, commanding great respect from everybody,” went to the kitchen and picked up the recipe book his mother had written in Hungarian. She then “went to my parents’ bedroom and picked up a diary from our early childhood, then went into the former studio and took out a big paper folder and stuffed in it everything she could reach — lithographs, etchings, schoolwork.” He does not recall her last name, because nobody ever used it.

Fenves was liberated from Buchenwald in June 1945. A few weeks after he returned to his hometown, his sister showed up, liberated from Bergen-Belsen. Their father returned on a Soviet military hospital train, “totally broken physically and emotionally,” and he died four months later.

They were surprised to learn about the items Maris had rescued. But two years later, when they decided to escape Yugoslavia, they returned the recipe book and artwork to Maris, who took care of it until she was able to ship it to his sister in Chicago in the early 1960s.

In the ghetto, Maris had “brought us food occasionally,” Fenves said. “After the war, she and her husband helped us find an apartment.”

In meeting with Fenves, Shaya got “a glimpse into his life before the war and what life was like around the kitchen table.”

Through conversations, he “learned all sorts of stories of him going to the market with Maris and his mother, loading up on the seasonal vegetables,” bringing everything home to pickle and preserve.

Fenves set out to translate 13 of the 140 recipes, using high-resolutions scans of the cookbook, because the original is very fragile. Shaya was determined to bring some of Fenves’ childhood dishes back to life, 75 years later.

After Fenves translated the recipes, the battle was not over. “A lot of them are just a list of ingredients,” Shaya said. “There aren’t many directions on technique or oven temperature.”

As Shaya experimented in New Orleans, he packed the creations in dry ice and sent them to Fenves for critiques and feedback, “and I’ve been making adjustments.”

Fenves remembered the potato circles, which he said was always made for guests, not for the kids.

A favorite was a turkey dish where the meat was ground and then placed back on the bone and baked. There were also semolina sticks, which Fenves told Shaya were supposed to resemble fish sticks. Shaya said it was essentially a cream of wheat, cooked down, chilled, cut up and lightly fried. “It’s one of our favorite snacks around the house now,” Shaya said.

Fenves said Shaya’s re-creations of the turkey and semolina sticks were “very authentic.”

Another recipe that was selected was a walnut cream cake, which is actually acceptable for Passover and is gluten-free. When Shaya saw the recipe, “I was really blown away. Five cups of walnuts?” But in his research, he found out that walnuts play a large role in Hungarian cooking, and he recalled his Bulgarian grandmother grinding walnuts through a meat grinder. Shaya explained that it allows the cake to rise and have a lighter texture. “It was a technique from the cookbook that really resonated with my grandmother’s cooking,” he said.

During a recent online conversation hosted by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Fenves sampled Shaya’s version of the cake.

While some of the dishes Shaya has made “were exactly duplicated as I remember,” Fenves could not “isolate the memory” of the walnut cake.

Fenves thanked Shaya “for your interest and persistence in reviving these recipes and reviving these memories.”

Museum historian Edna Friedberg said the recipe books show how many aspects of life were lost in the Holocaust, and efforts like this shine a light on the vibrant Jewish life that existed before the war in Europe.

Even in the darkest times, Fenves said, food was an inspiration. At the youth barracks in Auschwitz, “you stayed there until you died of starvation,” he said. They would remember foods that they had eaten and would make up stories of the meals they would order after being liberated.

Shaya said “this entire experience has not only inspired me, but so many of the chefs I work with.” He plans to feature some of the dishes on the menu at Saba, his Israeli-style restaurant in New Orleans, “as a Fenves family recipe, and be able to tell the story to our guests.”

Shaya said this project has been “one of the most gratifying and impactful things I’ve done in my career.”