New book chronicles Sue Eisenfeld’s (self-)discoveries in Dixie

Growing up in Philadelphia, the idea of Southern Jews never entered Sue Eisenfeld’s mind. In that atmosphere, Jews had come to America from Europe in the beginning of the 20th century and settled in the north. The South was this far-off land, filled with racists and Klansmen, certainly inhospitable to Jews.

Fourteen years after moving to Virginia, she and her husband, Neil, made their first visit to Richmond, and as one who enjoys exploring Jewish cemeteries, she went to an historic one there.

The dedication date was 1816.

And… there was a Confederate Jewish cemetery.

“This was far away from my world experience,” she said.

After growing up steeped in the history of the Revolutionary War because of living in Philadelphia, “I had lived in Virginia for 15 years and had become interested in the Civil War, because that is inevitable if you live in Virginia,” she said.

Nobody had ever mentioned the idea that Jews lived in the Confederacy, let alone fought for it. Thinking of the lessons of Passover, she wondered how that was even possible.

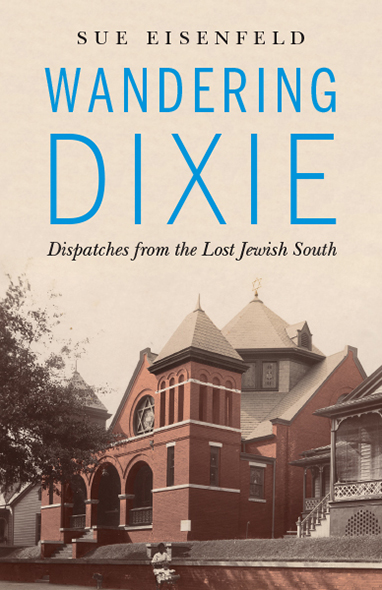

With an interest in history, and an emphasis on civil rights history because she had long heard stories of “second cousin once removed, by marriage” Andrew Goodman, who was murdered in Mississippi in 1964, she and her husband set out on visits to that strange land, the South. The result is “Wandering Dixie: Dispatches from the Lost Jewish South,” which was published on April 2.

Eisenfeld is a faculty member at the Johns Hopkins University MA in Science Writing Program, and a freelance writer.

The book chronicles not only her search for the Jewish South, but reflections on her own identity, from trips they took between 2015 and 2018.

Because pivotal moments in that timeframe include the 2015 Charleston church shooting and the 2017 white supremacist show of force in Charlottesville, political comments about the emboldening of extremism does creep into the narrative on occasion.

They wanted to travel the civil war sites in the South, but now that she knew there was Jewish history to explore, “I knew that I wanted to have a Southern Jewish experience… Once I got the idea of Southern Jews in my head, that definitely was driving my trip.”

She visited Charleston, one of the oldest Jewish communities in the country, in 2014. “Hearing Jewish people with a Southern accent when I went to Charleston and had my introduction to Southern Jews, I had never heard that before.”

While many of the stories seem spontaneous and she did, in fact, not arrange a lot in advance, she had contacted the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life in Jackson, where she got a long list of contacts, “not really knowing where I would show up. I had a lot of names in a lot of small towns,” and many that she did not get to.

“I’m happy that when I called these folks they were home, answered my call and were so receptive to the spur of the moment visits,” she said. When she was in Selma, “if Ronnie Leet hadn’t responded to my email that night I would have been leaving town the next morning” without learning about Selma’s extensive Jewish history.

The book starts off in Eufaula, where she meets the town’s remaining Jew, Sara Hamm.

She juxtaposes a Southern Jewish story with broader American history. She details how Julius Rosenwald of Chicago worked with Booker T. Washington in Tuskegee on the Rosenwald Schools, ultimately building over 5,000 schools for rural blacks throughout the South, one of which she visits. She then discusses another Tuskegee story, the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

Additional anecdotes take place throughout Louisiana, in the Mississippi Delta, exploring communities during the Southern Jewish Historical Society conferences in Nashville and Natchez, and journeys through South Carolina and parts of Virginia.

Meeting with Leet, for the first time she “got a different side of the (civil rights) story than I’d ever heard before,” how Southern Jews were caught between the segregationists and the civil rights movement, and how Northern Jews were complicating the situation.

While on her tour, she visited the site where her cousin and two other civil rights workers, Michael Schwerner and James Chaney, were killed.

“It was very easy as a Northerner to relate to the story of Andrew Goodman” and go to the South with that view of the civil rights struggle. She never thought of “the disconnect” in the views between Northern and Southern Jews. “They weren’t adversaries but they came to the situation with different world views,” she said.

A lot of life is like that, she said. “People get a world view based on where they live and what experiences they have.” For her, “a lot of this book was taking me out of the environment I had grown up and putting myself in a different environment with open ears.”

With that in mind, the book was really written for the Northern Jew, she said. “Southern Jews already know all this. Maybe they will find it interesting to read about my journey.”

She hopes that people will be inspired by the stories and seek to financially support some of the places that are still open and could use support.

“I’m hoping to share my story as an entrée into learning even more about the Jewish South,” she said.

While she describes herself as “non-observant” Jewishly, though she grew up in a Jewish home where relatives spoke Yiddish, the journey affected her Jewish identity. “I’ve always lived in places where there were lots of Jewish people and lots of synagogues. It never felt to me like something I needed to do because it was about to be lost.”

Seeing the small communities and places “that have a sense of loss,” it “made me realize not to take Judaism for granted.” In those communities, “it really takes each person to keep it alive.”

The experience “opened my eyes to a portion of history I was unfamiliar with, and now I’m interested in learning more and being part of my culture a little more.”

Though she wrote a book about it, she feels she would not have gotten as much out of the experience had she settled for just researching and reading. The highlight was “talking to people who were part of those events,” and there is value in going “to places with my own two feet and get a sense of history by being somewhere.”