Getting together for lunch: Reflecting on civil rights sit-ins in downtown Birmingham

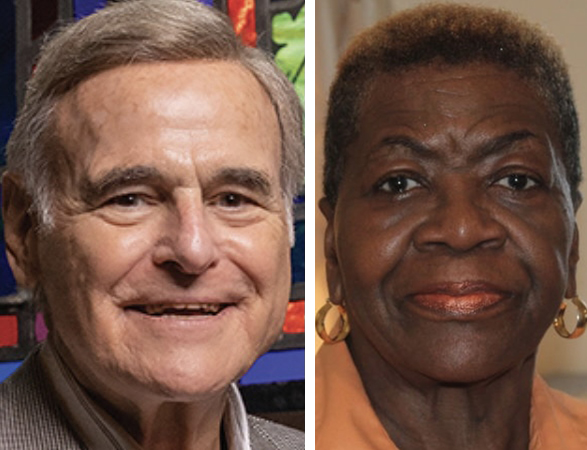

Michael Pizitz (Temple Emanu-El photo) and Frances Foster White (Birmingham Times photo/Ariel Worthy)

By Richard Friedman

It was a time long ago. So much has changed that it’s hard to remember such a situation once existed. But it did.

For decades there was a brutal segregation barrier in Birmingham and much of the Deep South that reflected an unyielding determination by the white establishment to keep the races separate in every facet of life.

Not only that, the intended message at every turn — delivered forcefully and at times violently — was that whites were superior and Blacks were inferior.

What drove Birmingham’s system of segregation was the belief that white dominance was inherent in the natural order of things; that African Americans were to be controlled no matter what the cost; and that access by African Americans to better education and equal economic and political opportunities would weaken the dominating grip of the white power structure on the city and its surrounding area.

This and more led to Birmingham’s emergence as one of America’s primary civil rights battlegrounds.

It also led to a fateful day in August of 1960 when the lives of Frances Foster White, an African American teenager at the time, and Michael Pizitz, a younger member of one of Birmingham’s most prominent retail families, became linked — leading to a friendship six decades later that neither could have imagined.

It was on that day that Foster White and other young African-Americans, who had been coached and prepped, entered Birmingham’s downtown department stores to intentionally violate the city‘s segregation laws, risking jail time, but determined to correct decades of injustice by launching another assault on the city’s oppressive Jim Crow laws.

“Didn’t Make Sense”

Foster White, whose family lived next door to the legendary Birmingham civil rights leader Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, planned to integrate the downtown Pizitz store’s in-store restaurant. For her, the assignment was personal.

“My family and I had shopped at Pizitz my whole life. What I didn’t understand was how we were allowed to spend our money in the store but could not eat in the restaurant,” she recalled. “It didn’t make sense to me.”

After she seated herself in the store restaurant, a Pizitz employee immediately understood what was happening and told Foster White that she needed to go down to the basement “where the n——s eat.”

The Birmingham teenager refused, police were summoned and she was taken outside where none other than Eugene “Bull” Connor, the city’s public safety commissioner and the face of segregation, was waiting.

Her belief, then and now, which she tries to impart to young people today, is “If you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything.” And indeed she stood tall that day, unafraid.

She and the other Black teenagers who tried to desegregate the eating areas at the other stores that day were herded into a police vehicle and taken to juvenile detention for the night, something they had expected and been prepared for.

Michael at the time was in his 20s and his father, Isadore, was running the business, which was started by Michael’s grandfather, Louis.

The Pizitz family, one of Birmingham’s most prominent Jewish families, was one of the state’s major retailers. The family had five stores in the Birmingham area and others throughout the state, with the downtown store serving as their flagship store.

Reaching Out

The Frances Foster White-Pizitz linkage might have ended in 1960 had not Birmingham’s WVTM-TV (Channel 13) decided in 2021 to do a story on Foster White and the day she tried to desegregate the Pizitz restaurant.

Two of Michael Pizitz’s daughters were watching the news that day and called him immediately. He then watched a video of the story himself.

After thinking about it, he decided to reach out to Foster White and connect with her, starting with a lunch — which she said should be at the Pizitz Food Hall, since that is where she had been arrested. Their getting together was chronicled by the station, and a fascinating and moving half-hour conversation can be viewed on its website.

The conversation was warm and reflective, and a powerful encounter for each of them.

Foster White recalled the drama of that August 1960 day. Pizitz explained the pressure his family and other downtown merchants, many of them Jewish, faced from both the Black and white communities.

He also recounted the coordinated effort by the downtown merchants not only to eventually desegregate their restaurants and restrooms but also to move African Americans into sales roles, another goal of civil rights activists.

“Segregation was wrong,” Pizitz said. “We all knew that. But if any store desegregated by themselves, it would face harsh and potentially violent reprisals. That’s why almost all of the downtown stores decided to do it together. So no one family or store could be singled out.”

The best part of the story, aside from the dramatic racial changes that have taken place in Birmingham since the 1960s (even though Foster White and Pizitz agree more changes are needed), may be the friendship that has developed between these two.

They talk regularly, get together for lunch and have become genuine friends; a relationship that has brought both of them great fulfillment.

One could even say that their story is a reflection and validation of the truth that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. put forth in his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” written in April, 1963:

“All men are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be.”