Groundbreaking partnership quietly defied the days of segregation

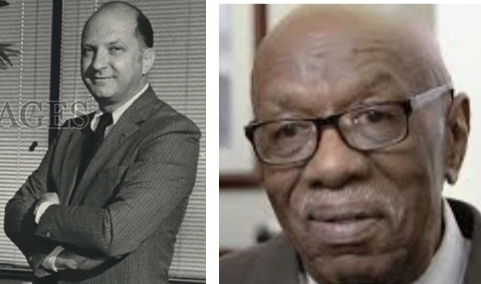

Cy Steiner and Shelley Stewart

By Richard Friedman

It was 1958. Not an easy time for Blacks in the Deep South.

No one knew that better than Shelley Stewart, a young Birmingham-based African-American disc jockey who was gaining a wide following across the region.

He found himself in Shreveport one day, sent there by his parent company, which owned stations in Alabama, Arkansas and Mississippi, to help get a new station off the ground.

Stewart got there and needed a necktie. So he walked into a men’s store. There were three salesmen on the floor, all white. None of them would even say hello.

Then a fourth salesman walked out of the bathroom, a young white man. He greeted Stewart courteously, saying to him, “Can I help you, sir?”

Stewart introduced himself and told him that he was a disc jockey and radio announcer who had been sent to Shreveport to help establish the new station.

The white man stuck out his hand. “Welcome to Shreveport,” he said. “My name is Cy Steiner and I‘m Jewish.”

Igniting a Friendship

That chance encounter birthed a partnership that would change both of their lives, launch a stealth attack on Birmingham’s iron wall of segregation and ignite a friendship that would leave a lasting legacy.

Steiner was from New York and his wife was from Louisiana which is how, fresh out of the Army, he had landed in Shreveport.

They chatted a bit while Stewart picked out his tie.

Stewart saw something in Steiner. He went back to his bosses and convinced them to hire Steiner to sell advertising for their new station, even though this New York transplant had no ad experience.

“In those days, even though these were African-American stations appealing to African-American audiences, the advertising sales force was white,” Stewart recalled in a recent Zoom chat.

The Black stations wanted white advertisers. Yet most white businesses at the time refused to deal with Black salesmen.

So Steiner came on board.

An Idea

After a few months, Stewart saw Steiner’s potential and recruited him to come to Birmingham, a larger market, where he felt Steiner could really make his mark.

It wasn’t long after that, that Stewart, who had become a major radio personality famously known as “Shelley the Playboy,” approached Steiner with an idea. He said they should go into business together, starting their own marketing and advertising firm, with Steiner as the face of the company and Stewart as a silent partner.

He proposed this arrangement because he knew that many in the Birmingham business community would be uncomfortable with a white man and Black man joining forces, especially if the Black man was Shelley the Playboy.

The product of an incredible personal story, filled largely with tragedy, difficulty and disadvantages, Stewart, a proud, visible and determined Black man, had become a lightning rod for people such as Birmingham’s segregationist public safety commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor and Alabama governor George Wallace.

This was the 1960s and Stewart was using his widely listened-to show to energize the Civil Rights movement, often in code. He also used his show to introduce white teenagers to soul music, and raise money from whites to help fund the African-American struggle for equal rights.

Salt and Pepper

In the midst of these tumultuous times, Stewart and Steiner saw a business opportunity — and how their skills could complement the other’s talents.

Eating together one day as they were evolving their vision, Steiner pointed to the salt and pepper shakers on the table.

He then removed the salt, to illustrate that both are needed for seasoning meals. Then he put the salt back and removed the pepper. “Shelley,” he said, “I’m the salt and you’re the pepper. Our agency needs both.”

Together they formed their own advertising and marketing company. Yet because of the tenor of the times they called it Steiner Advertising to camouflage Stewart’s involvement. Their enterprise grew and eventually became O2 Ideas, a nationally-respected advertising firm with a large and diverse client base.

“We built the agency together. At the heart of it was our salt and pepper philosophy — but we also knew how much pepper and how much salt.”

The two friends also talked a lot about racism and white supremacy, often over wine. Stewart, who already knew some of Birmingham’s downtown Jewish merchants, gained a greater appreciation of the Jewish community and Jewish experience as a result of his talks with Steiner.

Steiner, in turn, gained a deeper understanding of Stewart’s journey. At age five, Stewart watched helplessly as his alcoholic father murdered his mother with an ax. He would become homeless.

Stewart was eventually taken in by a white family. They gave him opportunities that would nurture his intelligence and talents, and ultimately transform his life. Stewart recounts his remarkable journey and against-all-odds business success in his book “Mattie C’s Boy,” as his mother’s name was Mattie C. Stewart.

Time Had Come

In 1992, Steiner died. Shaken by the loss of his dear friend, Stewart knew that for the good of the agency the time had come for him to step forward and become visible. He did, helping to lead the agency publicly until it was sold in 2015.

The Stewart-Steiner partnership was unique for its time, though Stewart stressed that the two joined forces not to break new racial ground but to create professional excellence and make money.

“We were a business. Our commitment was to provide excellent service to our clients. It was not to engineer social change.”

Yet, at the same time there were certain clients who knew that Shelley the Playboy was Steiner’s partner and they were comfortable and even enthusiastic about that.

Author TK Thorne, in her recent book “Behind the Magic Curtain: Secrets, Spies, and Unsung White Allies of Birmingham’s Civil Rights Days,” sees their joint enterprise, which she writes about in her book, as “unique and groundbreaking — almost unheard of.”

Thorne said “I believe it also reflected the fact that a lot of Jewish people in the community at that time would have liked to have done more, both for and with the African-American community, and done it openly.

“But at the time such activity and visibility could have affected their own businesses, families and even their safety.”

More than 60 years later it is hard to imagine that those bad old days even existed, given the changes in Birmingham’s business and civic culture, even though challenges still remain.

Steiner has been gone for 30 years, and Shelley the Playboy is now 87.

As he looks back, he thinks one reason Steiner was so warm and courteous toward him on that day they met, was that he was from New York and had grown up in a more liberal racial climate.

Even in his older years this legendary radio personality’s magnetic presence has not waned; his narratives are passionate and compelling and his memory is crisp, especially when talking about Steiner.

In a life filled with remarkable chapters, Shelley Stewart will still tell you that hands down, without a doubt, one of the most remarkable chapters of them all began the day he walked into a Shreveport men’s store looking for a necktie.

“Not only did we become business partners, we became friends — and brothers.”