Jewish, Black voices from past provide pathway to future

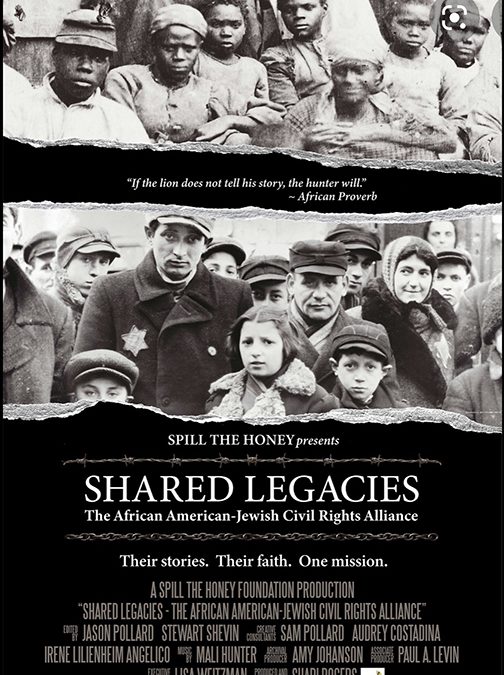

“Shared Legacies,” a new documentary highlighting the relationship between Blacks and Jews during the Civil Rights era, and how Jews supported the Black community during their time of struggle, was the focus of an online program Aug. 27, sponsored in part by the Atlanta-based Israeli Consulate to the Southeast.

Included on the program, which was oriented toward students, were former Civil Rights leader, Congressman, Atlanta Mayor and U.N. Ambassador Andrew Young, and former American Jewish Committee Director for the Southeast Sherry Frank, who are both featured in the documentary. Also on the panel was basketball great Isiah Thomas.

Spill the Honey Foundation and Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel at Morehouse College partnered with the Consulate. Shari Rogers, founder of Spill the Honey Foundation, wrote, directed and produced “Shared Legacies.” Rev. Lawrence Edward Carter Sr., dean of the Martin Luther King Jr. International Chapel since its founding over 40 years ago, is playing a pivotal role in the partnership as well. The Aug. 27 program was one in a series of offerings commemorating the rich legacy of collaboration between Blacks and Jews.

One moderator of the program was Wendell Shelby-Wallace, a 27-year-old Black man who works for the Israeli Consulate. His questions were probing and thought-provoking, and played a role in Young and Frank sharing highly-relevant insights, looking back on the Civil Rights movement and forward regarding Black-Jewish relations. His co-moderator was Blake Weissman, a Jewish student at the University of Michigan who is Spill the Honey’s national youth president.

Young was asked how he managed to work with people of differing points of view throughout his career and what advice he could give when it comes to negotiating differences of opinion with others, especially in today’s tense and divisive environment. To answer, the former U.N. Ambassador reached back to his childhood. “I was born in New Orleans in 1932, 50 yards from what served as the Nazi party headquarters, which was the German American Bund. In 1936, when I was four years old, my father had to explain to me what Nazism and white supremacy were.” His dad called them a “sickness” and then gave his son some advice, which Young has carried to this day.

His father told him, “You don’t ever get angry at sick people. Don’t get mad, get smart. Always be polite, never show fear. You know that God made all the nations of the world of one blood, but they don’t want to admit that and that is their problem with God. You are going to have to learn to live with people who are different and don’t like you, but the one thing you should never do is never get upset, emotional or angry.”

Young’s father was a dentist in New Orleans, and the dental suppliers he used were largely Jewish. Through those business relationships, friendships were formed. “So I grew up in a community that was bound together by common beliefs.” He recalled that one of the first integrated meetings he attended, when he was 12, was a gathering of the National Conference of Christians and Jews. He also said that he would not have become mayor if people such as Sherry Frank, his fellow panelist and a long-time Atlanta Jewish leader, had not helped him.

The former mayor was asked how to have important conversations with people despite disagreements. He said, “The challenge is simply to listen to each other. Let people air their differences and then at the end after they share their differences… you create a situation where people realize no opinion is set in stone. People are constantly growing and by listening to differences, you learn more about yourself and… learn to admit the weaknesses of your own position.” This approach, which is not only applicable to tension that sometimes arises in the Black-Jewish relationship, but in other relationships as well “keeps you flexible and enables you to grow.”

Frank, a now-retired long-time director of the American Jewish Committee’s Atlanta-based Southeast office, recalled forming the Atlanta Black-Jewish Coalition in 1982. From the beginning, she said, the late Congressman John Lewis was an inspiration, serving as co-chair. The work of the coalition continues today and is “alive and thriving.”

She also was asked what are effective tools for breaking through differences when the parties might not see eye to eye. “I believe the way to build coalitions is to get to know each other one to one on a personal level.” People need to feel comfortable talking to one another honestly and be encouraged to understand one another’s key issues, stressed Frank. She referred to “creating a table to hear each other” and again praised Lewis because of his ability to reach out to others and understand their histories.

Thomas, a legendary collegiate and professional basketball figure, reflected on his youth growing up in Chicago. “The Black and Jewish communities have always been together, particularly connected to sports,” he said. “In basketball, there were important figures” and, in particular, he mentioned with fondness Abe Saperstein, the Jewish owner of the Harlem Globetrotters.

Thomas said that in basketball Blacks and Jews have always interacted, noting that in the 1940s and 1950s there were outstanding Jewish players who others wanted to emulate, and today Jews are among NBA team owners. Through this mutual involvement in sports, the values that Blacks and Jews shared became evident, on issues such as voting rights and human rights, and especially both groups “wanting to be the best that people can be.” Thomas, who grew up poor in Chicago, eventually became part owner of an NBA team himself.

Worth Watching

The film “Shared Legacies,” which was the catalyst for this online discussion, is an outstanding production well worth watching.

Parts of the film focus on the Civil Rights movement in Alabama and Mississippi. Highlighted were long-time Birmingham rabbi Milton Grafman’s out-front push for Civil Rights and excerpts from a famous Rosh Hashanah sermon he gave calling on his congregants to stand up and be counted in the wake of the 1963 Birmingham church bombing that killed four young Black girls.

The film also highlights the 1964 murder of two young Jews, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, who had come to Mississippi to help Black citizens register to vote. Black activist James Chaney was also was murdered with them, in one of the most memorable and violent racial crimes of that time. The murders of Goodman, Schwerner and Chaney are often invoked to reflect the courageous willingness of Jews to stand with Blacks on the front lines of the Civil Rights struggle.

The film “Shared Legacies” also suggests that the Black-Jewish alliance that was forged during the Civil Rights era began to fray in the early 1970s, in the wake of the deaths of the two leaders seen as most pivotal to the partnership — King and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel.

In addition, the film suggests that urban tensions, which have sometimes pitted Blacks and Jews against each other, played a role. The film also didn’t shrink from the tensions that have been caused more recently as some Black activists link the struggles Blacks face today with the plight of the Palestinians, portraying Israel in a harsh and unfair light.

These are all complex issues, though the words spoken during the program offered inspiration and advice. Especially pertinent were the welcoming comments from the Israeli Consul General to the Southeast, Anat Sultan-Dadon. She said, “I look forward to the discussion of the history, present and future of Black-Jewish relations.” To that, Shelby-Wallace, the Consulate’s Director of External Affairs, who is responsible for outreach to the African-American, Hispanic, LGBTQIA+, Christian and Muslim communities, added, “Tonight we are focusing on ally-ship and talking about what that means.”

(If you would like to view the film “Shared Legacies” and/or view the discussion highlighted above, contact pr@atlanta.mfa.gov.il)

NAACP endangers Jews of color and all people by demanding anti-Israel arms ban

Read more